Back when I was still writing my little music blog about my most embarrassing favorite songs, I wrote a piece about The Beatles’ “The End.” (And while it is counterintuitive to think that would be an embarrassing favorite song, you’ll have to read it to understand why.) Megan plays a part. It was the last piece I wrote for that blog before she left us. I have since unpublished that collection.

Here’s The End if you’d like to read it.

—

When I found out Paul McCartney would be playing Coors Field on October 11th, 2025, I briefly considered attending, then quickly assumed tickets would be astronomical and talked myself out of it. Plus, I knew he would play a bunch of Beatles songs and that it would take all I could muster to not sob through the whole damned thing.

There is a nasty side-effect of my sobriety which I cannot fully explain. Moments arise during concerts in which I lose control of my emotions, overwhelmed by something I probably blunted with gallons of Miller Lite in the hazy old days.

A line from “Do You Realize” during a Flaming Lips show unexpectedly reduced me to tears. “Elderly Woman Behind the Counter” at Pearl Jam had me in a puddle. “Born to Run,” of all things, flattened me during Springsteen’s encore.

It could be that I’m just too sensitive, or fundamentally lack control. If I’m being kind to myself, I wonder if it might be a brief connection to something higher. My old counselor Richard said it was a brief glimpse of pure love, and that I should not fight it or try to control it. Instead, just ride it.

Easier said than done.

—

I had three basic rules for my daughters growing up, instilled in them at an early age:

- Always keep a whole chicken in the freezer (advice borrowed from my Granny.)

- Know how to change your own flat tire.

- Never trust anyone who doesn’t like The Beatles. You can be acquaintances, even friends, but know that when it comes down to it, they can’t be trusted if they don’t like The Beatles.

I began playing Beatles songs for the girls before they could talk. Yellow Submarine was a standard around our house. When our elder daughter was old enough to understand that her mom and I were constantly going to Red Rocks for concerts, she wanted to come as well. (At age 4, she was stomping mad about me seeing the Beastie Boys there in 2007 without her.)

To solve this problem, we ended up seeing 1964, The Beatles tribute band, at Red Rocks annually so the girls could get the full Red Rocks tailgate and concert experience (within reason.) They loved it. The event became a cherished tradition among several of our friends and their kids as well.

Once the girls each became independent young women, their Beatles evolution continued on its own. Lindsey’s second vinyl record purchase ever was Revolver. Megan loved “Blackbird,” among others. She also had several Beatles discs in her “vintage” CD collection.

We watched The Beatles: Get Back as a family when the documentary premiered. We discussed the alchemy on display in the formation of songs, the complicated interplay between the four members, and the spark Billy Preston created when he entered the sessions.

As they each matured, I began to lose touch with their musical journeys.

Going through Megan’s CDs in her mom’s garage after her death, I picked up the jewel case for All Things Must Pass, George Harrison’s solo masterpiece.

Turning to Lindsey, I said, “Why did she have this?”

“She loved George Harrison.”

I never knew. I so badly wish I had.

—

“You’re not gonna like this, but I’m going with a group of friends to Paul McCartney at Coors Field.”

“What?”

It was the tone of that “what,” the exasperation, the incredulity that I would go without her, that hit me like a truck.

When I had finally decided to buy tickets, I found an unbelievable deal on two along the right field line of Coors Field. They fell in my lap. Unforgivably, I hadn’t thought of asking Lindsey. I hadn’t thought of lots of things lately. Trying to keep life, work, and the case organized in my mind, the constant noise made even the simplest decisions difficult and kept obvious perceptions hidden.

Her response gnawed at me after that phone conversation. She hadn’t known about the show until I told her, and I knew she wanted in. I hoped a solution would come, and it did:

With a little help from friends, we were able to shuffle things around so that I had the extra seat for Lindsey. I texted her the day before the show and told her I had tickets for us, sitting together. She was noticeably ecstatic–rare for Lindsey, or for either of us–and my heart swelled. We made plans to meet up downtown before the show.

I found myself truly, purely excited about the concert, a feeling I’d not had about anything since some unknown time before February. This level of enthusiasm felt strange, unnatural. Guilt tagged along as it always does, but I was going with Linds and that made it okay. And I knew Megan would be with us.

I awoke Saturday morning and made a Paul McCartney mix on my phone while still lying in bed. “Lady Madonna,” “Let Me Roll It,” “Rocky Racoon,” “Hey Jude,” “I’m Down,” “Get Back,” “No More Lonely Nights” (whatever, I love that song,) the list went on and on. I hopped out of bed with a spring in my step, put the mix on the stereo LOUD, and began making pancakes and sausage.

Gotta get a good breakfast in—it’s Paul McCartney Day.

What I had temporarily forgotten is one of the primary rules of existence nowadays: any powerful emotions, positive or negative, leave an open door for grief to roll in like a squall. It’s as though my grief management force field has to shut down temporarily so that I can experience the highs and lows of normal experience.

As a result, I found myself sobbing uncontrollably over the griddle.

I’m excited. It’s okay. It’s okay to celebrate. I’ll be with Lindsey. Megan will be with us. It’s okay. Let Grief have its way, give it space, then let it pass on its own terms.

The grief continues to hit me in micro-attacks whenever it wants to. I try to give it all the space it needs when I have the rare occurrence of a quiet, solitary chunk of time. If I neglect it or try to muffle it in any way, the attacks become random and uncontrollable. The grief must be respected.

Okay. It passed. Now, get a grip.

I straightened myself up, noticed I’d nearly burned the batch of pancakes, turned off my McCartney mix, turned on College Gameday, and sat down with my pup for a lovely breakfast. I told myself this would be a good day, perhaps the first great day in a long while; however, I wondered how in the hell I would make it through the show without falling apart, repeatedly, in front of my daughter. But I resolved that the positives of the day would far outweigh the negatives. I would be okay.

But just in case, after I put on jeans, t-shirt, Megan’s LSU hat, and the Carhart sweatshirt the girls brought me from Paris last year, I stuffed a stack of Kleenex in my back pocket. I would not be caught unprepared.

—

The cloudy, cool, downright Liverpudlian day progressed. Eventually, our group headed downtown and watched football at a bar/restaurant near the stadium. I felt myself getting into the groove of the day and sharing the energy of my compatriots, too excited to see Paul McCartney in person to worry about anything else. Lindsey met up with me after spending the afternoon with her mom. To my joy, she was visibly excited and upbeat. We walked with the throngs over to Coors Field.

Having attended countless concerts, it’s uncommon for me to have a hard time coming to terms with the reality that the artist who created the songs is there on stage, but Paul fucking McCartney walked on the stage in front of us and was about to play real, live Beatles songs. Songs he wrote with John, George, and occasionally Ringo.

He opened with “Help.” I heard Megan’s voice, as clearly as if she were right next to me:

“It’s Paul McCartney!”

She got it, and she was as blown away as we were. She was with us.

The show progressed. The intensity of emotion did not overwhelm me; I rode it like a surfer on a wave. When Paul was handed a Martin acoustic guitar, the stage went dark, save a single spotlight. His fingers played the delicate opening chords of “Blackbird.”

It was too much. I could feel the long, deep gulps; I edged towards convulsion as the song went on. I couldn’t look at Lindsey. The astronomically high young tourist couple next to me (who couldn’t figure out how to light their second gigantic dispensary joint) didn’t notice me coming apart. I could feel my chest shaking, trying to breathe. I hung on by a thread. But I made it through.

During “Get Back,” Lindsey leaned in, smiling.

“This is a Megan favorite. She LOVED this song.”

Lindsey felt her presence just as I did.

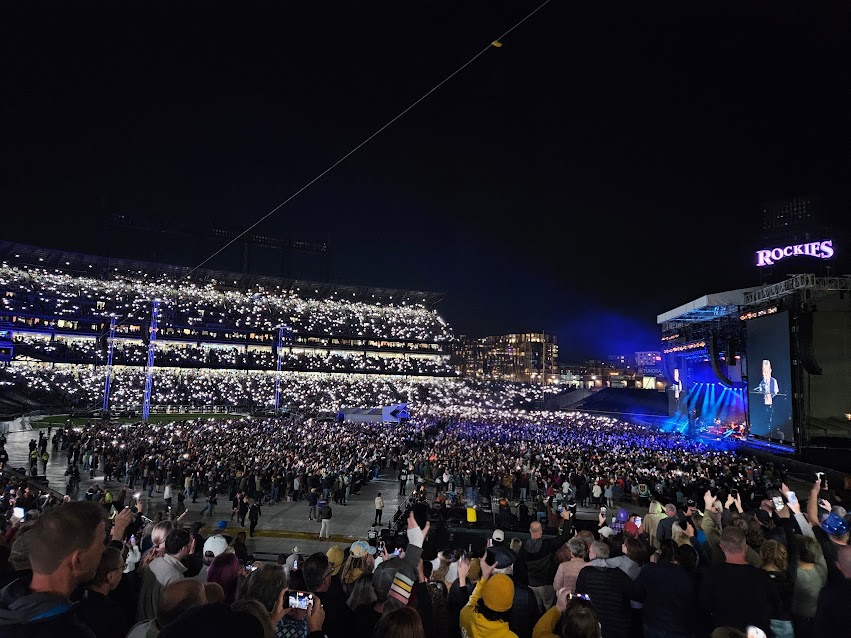

I had another little attack during “Hey Jude,” when 50,000 people all sang “Nahhh-Nah-Nah-Nanah-Nah-Nah” together, over and over. In all the concerts I’d ever been to, I had never seen anything like it. I tried and failed to comprehend what I was a part of–or partly a part of–since I was too breathless to sing along.

For the encore, Paul played a touching “I’ve Got a Feeling” with video footage of John merged in for a duet. Lindsey said she had to run to the restroom as the band went into the “Sgt. Peppers Reprise,” an appropriate and perfect song for ending the show on a high note.

We walked up the aisle from our seats to the concourse, empty but for a few fans walking by and an usher here and there on sentry duty in their Colorado Rockies caps and jackets. The bright lighting and pale concrete floor offered a stark divide from the darkness and light show of the event just a few feet away.

I told Linds I would wait for her there; otherwise, we’d never find each other when the show was over. “Sgt. Peppers” ended. The crowd erupted. I expected a “thank you” from the stage; however, after a short pause, the band went into “Golden Slumbers,” a song which has broken my heart since long before my heart was broken permanently.

“Once there was a way, to get back home.”

I had struggled with that lyric endlessly during the upheaval of our divorce a few years earlier. I had left my home. Our home. My mom had died years before; Dad was in the throes of dementia. Their house in Shreveport, my original home, had been sold a few years prior. (I have my parents’ Abbey Road album that Mom bought in 1969, the only one of their Beatles albums I ended up with.) “Golden Slumbers” always brought these losses, and by extension my lack of tether, into clear focus.

Surely they won’t do the whole medley.

They did. “Carry that Weight” was next, then “The End.”

I watched through a break in the crowd while standing alone on the concrete of the concourse, in the light, behind the stadium seats where fifty thousand fans were bathed in love, swaying along. I felt tears again. I choked them back.

An elderly usher lady standing ten feet away by a staircase looked at me; I knew it was her job to tell me to keep walking or return to my seat. But the way she looked at me, she could see me. I don’t know what she saw. I don’t know if my eyes were looking through her or begging for help. She started to issue her command, then paused. A delicate, sympathetic smile arose on her furrowed face. She held my gaze for a moment then slowly turned back toward the concert.

I stood alone, in that harsh light, while Linds was in the restroom and the crowd of fans stood just before me but seemed miles away. Alone. I had been able to enjoy the whole thing, temporarily letting go of pain and relishing the time with Lindsey, but during this expression of the last moment of The Beatles themselves, in the last moments of the concert, as the memory of telling a young Megan how important that upcoming lyric was to all our lives appeared in my mind, I had nobody to lean on, nobody to blame. No home to return to. No way to change the past. Alone. Force field down.

“And in the end, the love you take, is equal to the love you make.”

It had meant so much to me, this lyric. I once believed it was the answer to everything, every problem, every question. The Golden Rule. Since sobriety, I had tried to live by it. But now, I hadn’t the faith to know if it still mattered. It had not saved my daughter. Nothing had.

And now I was exposed, judged by fluorescent lights, unable to participate, unable to be a part of anything. Unattached to the concert, to the fans, to Paul McCartney, or to even to the elderly usher, I was stripped bare. I was nowhere. Nobody. Not a person, not a concertgoer, not a Beatles fan, not a friend, not a dad, simply a tiny speck within a familiar state of terror.

I grabbed a tissue from my back pocket, wiped my eyes and nose, and took a couple of deep breaths.

Why? What is the lesson here? Do those words still matter?

I didn’t have an answer. It was no longer that simple.

The attack subsided. Grief slid back into its cave, satisfied for now. The final crash of instruments ended the song. The crowd roared with its approval.

I turned to see Lindsey walking out of the restroom as the house lights came up. I felt the emptiness wash away, the stark moment of anguish gone, replaced with the warmth of her smile.

“That was amazing,” said Lindsey. “No ‘Eleanor Rigby,’ but no string quartet.”

“No ‘Yesterday,’” I said. “But yeah, no strings. Still incredible.”

“Incredible,” she replied with a smile.

Exhausted fans, faces aglow, began streaming out of the stadium seats into the bright concourse and on toward the exits.

Making our way to the spot where we were to reunite with the rest of our group, we discussed our favorite parts of the show, marveled at Lindsey’s new concert t, and watched humanity make their way out into the night. Soon, our group joined us. We headed towards the parking lot while talking, laughing, and exhaling from a monumental evening.

The End.

Wow! Just wow!Very powerful. Big hugs. Sent from Dave O’s iPhone

LikeLike

Joe, Beautifully and powerfully written. It definitely left me

LikeLike

These are gre

LikeLike